Ten Characters

YEAR: 1988

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 15

PROVENANCE

Consisting of the installations No 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, as well as The Man Who Saves Nicolai Victorovich, The Man Who Describes His Life Through Characters, The Man Who Collects the Opinions of Others and additional smaller rooms, depending on the location of the exhibition

EXHIBITIONS

New York, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

Ten Characters 30 Apr 1988 — 4 Jun 1988

London, Institute of Contemporary Art

Ilya Kabakov. The Untalented Artist and Other Characters at the ICA London 23 Feb 1989 — 23 Apr 1989

Zurich, Kunsthalle Zürich

Das Schiff – Die Kommunalwohnung, Zwei Installationen von Ilya Kabakov 2 Jun 1989 — 30 Jul 1989

(without No 9)

Washington, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Directions. Ilya Kabakov. Ten Characters 7 Mar 1990 — 3 Jun 1990

Toronto, The Power Plant

Ilya Kabakov/John Scott 15 Nov 1991 — 5 Jan 1992

(only: The Man Who Saves Nikolai Viktorovich, as well as Nos 20 and 21)

Not preserved as installation in this form

NOTES

See #’s 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

Not preserved as an installation in this form. The Short Man and The Man Who Describes His Life Through Characters are part of the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, USA, since 2000 and 2002 respectively

DESCRIPTION

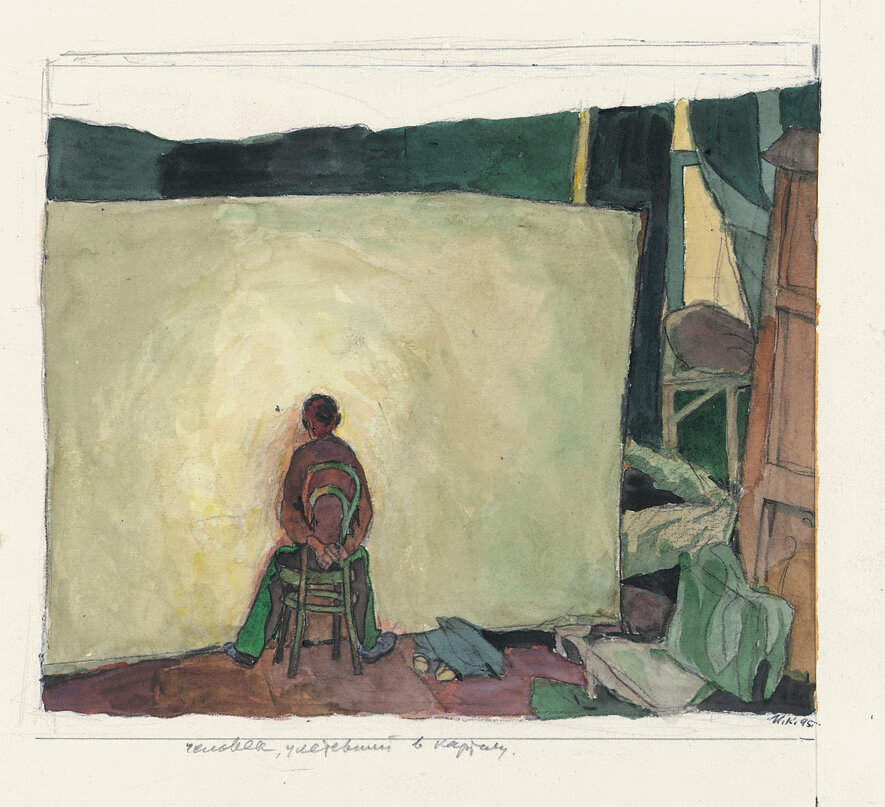

The installation Ten Characters was exhibited in Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York from April 30 to June 7, 1988. Two halls of the gallery were transformed into two large communal apartments. The first consists of a long corridor with rooms running along both sides, and a resident of the apartment lives in each room. The rooms have low ceilings (240 cm), just like the low ceiling in the corridor. The front wall of these rooms is missing, so that someone walking along the corridor can easily see everything in the rooms, and he can even enter them. The corridor ends in a large kitchen. This is a tall room (nearly 5-6 meters, the same as the gallery), and rather spacious (nearly 25 square meters), as opposed to the small rooms of the ‘residents.’ The corridor, the rooms, and the kitchen are all painted a dull, depressing gray color. Weak bulbs burn in the corridor, casing a dull light into the rooms, and they are therefore semi-dark. It is a bit brighter in the kitchen. The exact same kind of apartment, only a bit smaller, is constructed in the other hall of the gallery, and it is painted the same color. Hence, the viewer finds himself in spaces of differing heights as he views the installation; first he enters into the low corridor and into the equally low rooms, then he winds up in a relatively high-ceilinged kitchen, then he enters into the second, almost identical, kitchen, and then again finds himself in a low corridor and rooms with the same low ceiling. What is in the rooms where the viewer may freely wander, since not only is there no door on them, but the front walls are missing as well? (The exception is the room of the man who flew into space, because it is littered with boards.) In general, this corridor with the cross-sections of rooms slightly resembles either cages in a zoo, or open, unbarred jail cells, or perhaps furniture displays in a store that are separated from one another by walls and are filled with furniture – for the kitchen, bedroom, etc. This similarity with these places is emphasized even more by the brief descriptions hung near each room of the character of the resident living there.

But perhaps he doesn’t live here anymore, but rather used to live here? Each room really does contain a multitude of objects that belong to its inhabitant, but they are arranged in such a way that they are more like reminders of these people and their existence. The things have a memorial quality to them, as though we were in some home-museum, where we would be shown the bedroom, the dining room, the office of a famous poet, composer, etc. These objects are arranged in the exhibited room as they were during the life of the residents, but everything relating to their daily existence has been removed and the floor has been washed. This ‘memorial’ and ‘museum’ quality is especially reinforced by the lengthy explanations hanging on the walls that tell in detail, like a guide’s lectures (and in the same tone), all that the visitor has to know about each character here: about the details of his lifestyle, and most of all, about his main project that he lived with and that he left this life with, as well.

The thing is that each of these characters lived according to his own special idea, an idea that had consumed him entirely. We shall describe in detail the ideas of each of these residents. Here it is important to note that these characters themselves, their idea-fixe could only have emerged under the conditions created by a communal apartment. These ideas were engendered by the special atmosphere of this communal apartment; the main task of the artist here was to create the image of a communal apartment, its air. This task was resolved primarily by the layout, as well as the color of the walls, ceiling, and the lighting. The layout had to create the impression of a depressing, dead casement, not complex or confusing, but on the contrary, impoverished in its elementary quality. The color of the entire installation was the same: dark gray, cold, without any shading whatsoever. In terms of lighting, there were three types: the first type was the illumination of the corridor and the rooms, that could perhaps better be called ‘half-lighting.’ This lighting permits one to view only the exhibits and to read the explanations, but the corners and the corridor remained submerged in semi-darkness. The second type of lighting is the kind used in the two kitchens. Here it is stronger, but still not sufficient to dissipate the dreary atmosphere reigning all around. This light can be noticed from the ends of both corridors. Finally, the third type of light is that which is coming from the hole busted through the ceiling of the room of the man who flew into space. This light is extraordinarily bright, penetrating, it falls in a vertical column down onto the objects that are turned over and scattered about the room. This is the only blast of light in the whole installation, and it creates a contrast to the overall gloomy semi-darkness reigning throughout. Since the main ‘objects’ of the installation consisting of a few installation rooms were our 10 ‘heroes,’ we shall name each of them here in order:

The Man Who Flew into His Picture

The Man Who Collected the Opinions of Others

The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment

The Untalented Artist

The Short Man

The Composer

The Collector

The Man Who Describes His Life Through Other Characters

The Man Who Saved Nikolai Viktorovich

The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (The Garbage Man)

CONCEPT OF THE INSTALLATION

When I think about our life, one of the main images that unites everything is that of the communal apartment. After the revolution in 1917, we began to see ‘consolidation’ and ‘division’ of living space in all of our big cities, and especially in Moscow and Leningrad. People who lived in basements began to move into formerly ‘luxurious’ apartments. There was a shortage of living space, and numerous waves of people, both local and newcomers, were given the apartments that had been left empty by departing ‘bourgeois’ and ‘noble creatures’ by special ‘orders’ issued by organs of the new proletarian regime. However, people also simply moved into apartments without any kind of ‘orders,’ grabbing them up, and almost instantaneously entirely new associations of people formed in these twelve- and sixteen-room apartments, people who often didn’t even know who their neighbors were, what they did, where they worked.

The old tenants, if they hadn’t already left or hadn’t been destroyed by the new regime, were subjected to ‘consolidation,’ i.e. they ‘received’ one room in their former apartment and all others were given to new tenants. Under conditions created by the permanent housing crisis during the post-revolutionary and later the post-war periods (until 1953 there was virtually no mass-scale building of residential housing like there is now) a family lived in the same place virtually forever. One family was entitled to one room, and as the flood into the cities intensified, more and more members of that family and relatives moved into that one room. And the family to whom the room originally belonged itself grew, so that the number of inhabitants in the rooms, which were often no more than 10-12 square meters, grew each year. Three or four generations: great-grandmother, grandmother, father and mother, children, distant relatives – often lived in one room with no hope of ever moving out. Rooms that had been large at one time, 30-40 square meters, were divided by thin plywood partitions into smaller rooms in which families also lived and multiplied … Often these cells were no larger than 5-6 square meters, and two or three layers were built in them to accommodate everybody.

But, obviously, it was impossible to stretch, to enlarge the actual apartment, and the layout remained as it was when the ‘old’ owners lived there. A few words about that layout. Major urban construction took place in our big cities in the 1880’s and 1890’s, and the main type of construction were so-called ‘lucrative properties,’ i.e. buildings which had apartments that were rented out primarily to the well-to-do: lawyers, doctors, engineers, important functionaries, industrialists, etc. All of these apartments subsequently became ‘communal,’ but not only these. All one- and two-story buildings, often wooden, where families of bourgeois craftsmen, petty tradesmen, poorer bureaucrats, etc., lived before the revolution were also turned into communal apartments.

One room, on the bottom left, becomes the room for ‘common use.’ As a rule, it doesn’t have a window and tenants store heavy things or things they don’t need in it – dressers, shelves, old couches, tables, things that they can’t bring themselves to throw away but which block their entire living space. Communal apartments, more precisely, the number of their tenants, would have grown ad infinitum if there hadn’t been a regulation passed almost immediately after the revolution forbidding the arrival of new people from the provinces, and mostly from the villages, into the city – the ‘residence permit’ rule. Those who were already living in the cities were given the ‘right of residence’ for that living space which they already had, but out-of-towners could not obtain this permit. An exception was made for ‘specials’ – persons who were needed by the government, important functionaries who had been transferred from other cities. They received permission from the authorities – the right to an ‘order’ – i.e. the right to a room, and consequently the right to a ‘residence permit.’ ‘Residence permits’ are a part of our lives to this day. Current regulations allow a husband to register with his wife and vice versa, but forbid parents, children, brothers, and sisters from doing so, to say nothing of aunts and nephews. Residence permits are either permanent or temporary. One who has a permanent registration can live in his room until his death, someone who has a temporary one (for 1, 3, 6 months) must move out at the end of the indicated period or else he will be evicted.

The police vigilantly monitor and check to make sure that no one who is ‘unregistered’ is living in the apartment. And the neighbors also inform immediately on him. Furthermore, control of this is the responsibility of a special ‘authorized person of the apartment,’ selected by the entire apartment. This ‘authorized person’ informs his tenants of all the regulations and orders issued by the building or block authorities, i.e. the ZhEK (the Housing Authority). Incidentally, this name is continually changing. It used to be ZhAKT, now apparently it’s something else. This state institution sees to the sanitary condition of the residential resources – the working condition of the lavatory, toilet, heating system, repairs, and remodeling … But primarily it is responsible for the administrative documents concerning the apartments and their residents, residence permits, the issuing of certificates, the acceptance of appeals. The ‘authorized person’ informs the higher command of issues of the organization of daily life, he is also responsible for innumerable schedules, announcements, notices, for example, the cleaning schedule: who’s turn it is to take out the garbage and when, who is to wash the hallway, the kitchen, the lavatory. But, although it may be within the capabilities of a human being to draw up a schedule of cleaning duties and taking out the garbage, it is completely impossible to comprise such a schedule for the use of the bathroom and toilet (there are most often two separate rooms, one with just a toilet, the other with a bathtub and sink), which is mandatory for all, it is completely impossible and as a result it all ends up occurring haphazardly. And therefore everyone lines up in the morning with a towel over their shoulder to wash up in the bathroom, even though there is almost never such a line for the toilet. The tenants simply stand inside their rooms by the door, waiting to tell by the sound and footsteps that the toilet is free so that they can dash into it.

The tenants in a communal apartment are often divided into factions with each clan having its own leader and the war waged between these clans can be either concealed or overt, smoothly ranging from cursing to fist-fighting…

The cursing and abuse that is aimed at another are explicit, and one might say, of an analytical nature. And there is nothing surprising about this. Each person’s life is conducted under the intense scrutiny of all the others. Everyone lives as though they were under a magnifying glass. There are no secrets. Everyone knows who brought what home, who is cooking what, who had what shoes on yesterday and what they’re wearing today. However, oddly enough, this does not prevent certain tenants of a communal apartment from creating intriguing, even mysterious impressions. All sorts of myths which are often quite foolish and improbable develop and swell around this person. Thus, many are certain that in the second room from the door lives a genuine millionaire, and in the seventh room from the kitchen – a German spy, and next to him lives a real gangster, etc.

The apartment is filled with myths. But it is also filled with all sorts of junk and often the owners of the junk don’t know what to do with it. The entire corridor is filled on both sides with trunks, boxes, bundles, packages, all piled up and sometimes tied with rope. Above these piles, there is the obligatory coat-rack next to each door, and above it, there are more shelves with belongings, while bicycles, basins, and chairs hang on nails… But the apartment is exhausted not only by all of this junk and garbage but also from something else: from the incessant sound of voices be they shouts, the carryings-on of children or quiet conversations, which never subside neither day nor night, resounding from all sides, from the kitchen, the corridor or from behind the thin partitions of the rooms.

Just who rules this world? Without a doubt, a matriarchy rules in a communal apartment. Men feel like outsiders and almost never go into the kitchen, and they don’t look out into the corridor often, either. All contact is carried out by women, and the atmosphere depends primarily on them. Sometimes this is a wonderful world of mutual assistance – favors, treats, trusting conversations, and advice. And sometimes it is a very evil world of endless arguments, insults, animosity, and revenge that lasts, for years, where men are dragged in as ‘heavy artillery.’ Arguments arise over trifles – unreturned dishes, someone took too long in the bathroom, because of the dirt from ‘your guests’ feet.’ And it is always pointed out in the accusations that there has been a violation of a universally accepted moral. This moral is understood and clear to all tenants except to the one who is being accused of violating it. Therefore, arguments and the sorting out of disagreements usually takes place not one on one, but in the presence of all the other tenants to whom the ‘wronged party’ heatedly appeals, as though calling upon them to support the profaned truth. From the side, this is reminiscent of a Greek tragedy in which the chorus – collective reason – is supposed to sort out the problem and give its sentence. Often, however, the chorus doesn’t participate in this, and then the wronged party writes a detailed letter to the Comrades’ Court (a type of court made up of the neighbors and people from the ZhEK), as does the adversary, they collect evidence from other neighbors, each side from its own allies, and the whole affair is transferred to the ZhEK, then to the police, and then, if things get really out of hand (like beating or maiming) then to the regional People’s Court…

Images

Literature