The Man Who Flew into his Picture

YEAR: 1988

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 16

PROVENANCE

The artist

Version 1

Collection The Museum of Modern Art, New York, since 1992.

Version 2

Collection Sigmund Freud-Museum Wien, Vienna, since 1989.

EXHIBITIONS

Version 1

Ten Characters, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, 30 April – 4 June 1988 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters).

Ilya Kabakov. The Untalented Artist and Other Characters at the ICA London, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 23 February – 23 April 1989 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters).

Das Schiff – Die Kommunalwohnung, zwei Installationen von Ilya Kabakov, Kunsthalle Zürich, Zurich, 2 June – 30 July 1989 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters).

Directions. Ilya Kabakov. Ten Characters, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, 7 March – 3 June 1990 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters).

Devil on the Stairs. Looking Back on the Eighties, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 4 October 1990 – 5 January 1991; Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, 16 April – 21 June 1992.

From the Collection: Abstraction, Pure and Impure, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 29 October 1995 – 21 May 1996.

See No 15.

Version 2

Schenkung der Künstler John Baldessari, Pierpaolo Calzolari, Georg Herold, Jenny Holzer, Joseph Kosuth, Ilya Kabakov und Franz West an das Sigmund Freud Museum anläßlich des 50. Todestages Sigmund Freuds, Sigmund Freud-Museum Wien, Vienna, 23 September – 18 October 1989.

Foundation for the Arts, Sigmund Freud-Museum Vienna, Sigmund Freud-Museum Wien, Vienna, 21 November 1997 – 18 January 1998.

DESCRIPTION

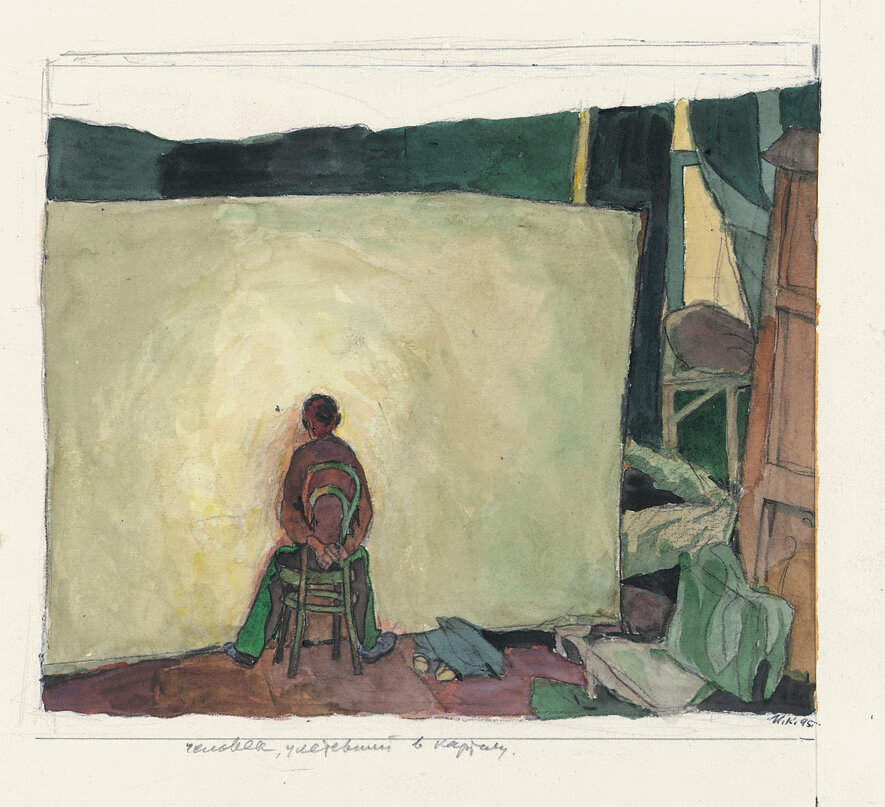

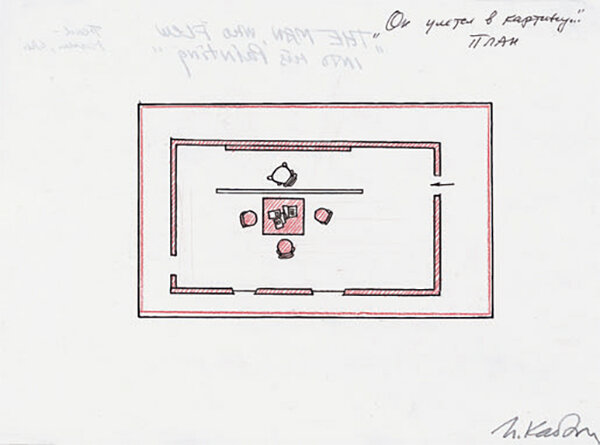

An enormous whiteboard stands diagonally across the room, inadequately lit by a weak light falling from above from the corridor. On the board, if you really scrutinize it, is drawn a tiny figure of a person only 5-6 cm big. It is drawn in a pale blue paint. There is an empty chair before the ‘painting.’ Various utterances, as a rule no more than a single line, written in neat handwriting, are arranged on the wall to the left. Closer to the exit, at the far right, is a screen-commentary standing on a small shelf, which tells in detail about the ‘main idea’ of the person living here.

ARTIST`S COMMENTS

I always remember myself not as a person of action, of predictable behavior, but rather as someone ‘thrust’ into some sort of ‘state’ from which everything then followed and occurred sort of on its own and for reasons which were inexplicable. The peculiarity of such a state is that I was in a state of total immobility, inactivity, as though I had been rooted to the spot, had frozen, not wishing and not able to act, but expecting that something would happen to me on its own. I always feared such catalepsy because I didn’t know how to overcome it, and it could last for an infinitely long time. (Therefore, by the way, I tried to think up all kinds of plans for myself so as to carry them out later on, not stopping until they were finished, so as to escape, run, from my ‘states.’) Of course, every such ‘state’ was not at all vague for me. Inside it were two halves, similar to two fighters grappling in the ring who are immobile only because one cannot overcome the other.

Here is an example. I would call one such ‘state’ which continually haunted me a ‘state of semi-culture.’ I was always certain that the entire ‘Soviet world’ – and I was a part of it – was something continually ‘semi-,’ ‘neither this nor that,’ consisting of a suspension of fragments and scraps of various cultures, notions, symbols, objects, rules. To a degree, such a conglomerate is sufficiently dynamic, excited, charged with energy: this is because the most ill-assorted and incompatible things which usually exist separately collide in it. And all of this is united by the strangest means: conjectures, imagination, ideology, exhaustion…

Among other ‘adhesive components’ used in ‘semi culture,’ what was important to me was what I called the concept of ‘intention.’ I’m talking about the following: in our ‘Soviet world,’ everything was of very bad quality, old, superfluous, broken. It was always very important to know the ‘indirect’ data on these things: how long would they work, who had repaired them and with what intentions – so that it would work, or not? Our citizens were very familiar with the presence of these ‘supplemental circumstances,’ an almost irrational component. It’s as though we grew a special organ for identifying it. Therefore we never trust instructions or documents with signatures, but rather we are guided by our own sense which was discussed above. We judge the quality of repairs in the apartment according to the manifestation or lack thereof of effort by the painter, the painting of a car by the effort of the specialist. For us, the effort itself replaces the ultimate result, the obvious reality.

And so, when I would make my paintings, I was also under the power of a similar criterion, entirely subtle and accessible only to an inhabitant of our world. Even inside myself, submerged in that air, I could not distinguish a painting that was actually well done from something that was done with a desire to ‘do it well.’ For there are many paintings that are ‘very good’ but that were done without that desire. Such sincere effort, diligence, becomes the most important sign of a good artistic work. And there’s something more than that. The intention to ‘do it well’ would overflow in me when I would begin to work. But this only led to the fact that I couldn’t differentiate between what turned out really well and what didn’t. The ‘desire’ obscured, replaced reality. It always seemed to me that things were going well, that everything was ‘turning out well’ and that – what’s worse – everything was ‘already finished.’ When I would put one dot on a board, while there was still only that one, I would think that everything had already ‘happened’ and that the work was finished. Then, in contemplating such an ‘empty painting,’ I would re-absorb that ‘desire’ which had filled me before I began to work…

… Everything was thus completely all right with me. But what was this for others – after all, could they see, understand that before them there was nothing except an empty cracked board, carelessly chipped, stained and sloppily painted with whitewash?

I don’t know. Probably, it appears to be nothing, nonsense. But I was completely certain that the painting ‘had taken shape.’ I believed. In the famous fairy tale about the naked king, I was on the side of those in the court, not on the side of the little boy. I knew and believed (I continue to believe even now), that if I really strongly believed that this was not an empty board, then it wasn’t.

… Years passed. Looking at these boards I continue to see something there. (Now I don’t remember what.) The energy of the desire has remained.

… Perhaps, the king really was wearing a suit? The most interesting thing is that the viewers (some of them, anyway) are ‘infected’ by this certitude, this illusion.

Images

Literature